I count examinations... as the enemy of education.

Which is not to say that I don't regard education

as the enemy of education too.

Mr Hector in Alan Bennett's The History Boys)

Preparing for AS and A Level English Literature

Think bored examiners,' says the 'meretricious but not disingenuous' Mr Irwin to his elite class in Alan Bennett's latest play. Of course, as an examiner myself, I would never suggest that you encourage your students to be merely 'showy and falsely attractive' for the sake of gaining better marks. But having pored over more A Level scripts in my time than has been good for my health, I believe there are a number of things you can do to help those eager souls in your classes (and perhaps even the not-so-eager ones) to do their very best.

For a start, you can drum into them that if the examiner can't read what they write they won't get many marks at all. If it's a struggle for me to make out the words because of poor handwriting or atrocious spelling, I'll lose the plot before the end of the page - and it's actually quite a good idea to keep the examiner following your plot. Not the plot of the novel or play, of course - believe it or not, we have read the books and don't need to be told the story again, thank you. However, if the answer has a clear structure and leads the examiner confidently to the conclusion, all the while answering the question, full marks may be the reward. Yes, we may appear a curmudgeonly lot, red-inked and red-eyed, but really English examiners are just ordinary English teachers like you, kind and generous and soft of heart who long only to praise and reward.

So how can your students bring out the best in the examiner - and in themselves? Some time ago, when asked to speak to students at a revision conference, I rashly stated that it was as easy as ABC:

Answer the question

Base it on the text

Communicate clearly, coherently and cogently

Nothing is quite this simple, of course - nor will these exhortations come like thunder-bolts of revelation to teachers. Let me explain why I think they are worth emphasising.

A version of this article originally appeared in English Teaching Online from Teachit in summer 2006. That issue also contained valuable advice on GCSE and A Level language revision.

The Principal Examiner will have spent many hours honing the questions so that they match the assessment objectives for the paper. Pick up the key words, stick to the question and you will be doing what's asked. Too many competent students (at least, they can write well and know the text) gain disappointing marks because they ignore the question. If you're asked about the presentation of Laertes, it's no use spending your time on Hamlet just because he's the one you really want to write about. Skilled candidates can think on their seats: they adapt their knowledge to meet the demands of the question. So the ways Hamlet reacts to Laertes and behaves in similar situations is of course very relevant, but keep your eye on the main thing: the question in front of you, not the one you did in the mock examination. Ensure students use the first few minutes for planning: they may be A Level students but many still rush headlong into a shapeless journey that leaves the reader struggling to see the point. Spend regular sessions planning model answers together - and writing introductions and conclusions. Do timed essays, too; these might seem chore, but students will be grateful for the skills.

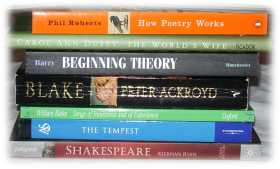

![]() Literature examinations are all about the text, aren't they? So, make sure they really know their books inside out, even if they can take them in to the examination. Learn some key passages - they'll thank you for that too - and use them. Don't write character sketches - this is literature, so support your points by brief but telling details and make it clear to the examiner that you realise there's an author at work, choosing words and actions for effect. Never make assertions - examiner-speak for bald and often dubious claims without support: 'Hamlet has an Oedipus complex' and that sort of thing. Discuss alternatives, show your independent judgement.

Literature examinations are all about the text, aren't they? So, make sure they really know their books inside out, even if they can take them in to the examination. Learn some key passages - they'll thank you for that too - and use them. Don't write character sketches - this is literature, so support your points by brief but telling details and make it clear to the examiner that you realise there's an author at work, choosing words and actions for effect. Never make assertions - examiner-speak for bald and often dubious claims without support: 'Hamlet has an Oedipus complex' and that sort of thing. Discuss alternatives, show your independent judgement.

Considering the reader is basic courtesy. If they've learnt how to plan, those flowing paragraphs should have the requisite topic sentences and connectives that link the answer into a seamless whole, with every paragraph directly related to the question. And make sure I can read it, please - if you use alternate lines, I won't mind. Do all this and I can write 'cogent, sophisticated' and other glowing words at the end (please leave me space to do this, you're worth it) and give you a good mark.

Well, it is A Level, of course, so it will take some practice - by your students. You've passed your exams, haven't you? You could try picking up a red pen and becoming an examiner yourself - you'll learn quite a lot and earn a bit too.